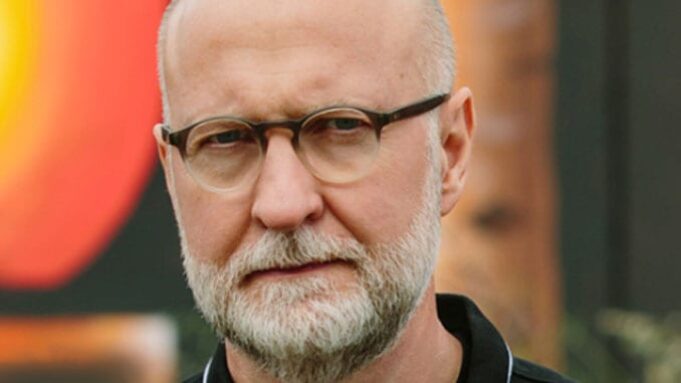

Performing Live: Bob Mould with Will Johnson at Headliners Music Hall, Louisville, KY September 17, 2019 by Keith Halladay

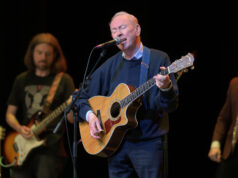

A single Fender 2X12 amplifier and a mic stand on an otherwise empty stage. Bob Mould appears, through the side-stage curtains, slinging a silver Stratocaster. He approaches the microphone, smiling: “Hi everybody!” Fiddles a moment with his guitar knobs. Then: “Well, let’s just get into it.”

The set starts with a crunch. “The War,” from 2014’s Beauty and Ruin. He’s 58, paunchy but hale, and bouncing around the stage like he rarely did as a much younger man. It’s an inversion of a rock-legend career progression: a typical Hüsker Dü gig of 35 years ago saw Bob standing stock-still, staring blankly into middle distance as he sang, while around him everything crashed, whirled, banged, and churned. This is the opposite. He has all the energy now, jumping, and turning and just rocking, while the overwhelmingly middle-aged audience, many of them veterans of the grittiest of mosh pits but beset now by trick knees and dodgy backs, sit serenely, but for involuntary foot-taps and gentle head-nods.

No break: right into “Flip Your Wig.” He’s supporting a new album, the excellent Sunshine Rock, but this set won’t showcase it. It’s a bit of this, a bit of that: some Sugar, a fair bit of Hüsker, and solo selections across the decades. Whatever he feels like playing.

And right into “I Apologize,” one of the tunes that first indicated, on 1985’s New Day Rising, that Bob’s sense of hook and melody would transcend punk noise and provide a blueprint for an entire generation of grunge and pop-punk bands. Here I do miss the full sound; I’m mentally filling in the absent bass and drums—mostly the drums— first with Grant Hart’s signature shimmer and then with Brendan Canty’s precision and power. But touring economics come first: to make this tour work, to make the journey from Germany worthwhile, it’s just him, his axe, and his amp. Very DIY. And very, very punk.

A breather. “Is the guitar loud enough?” It is, in fact, but he turns up anyway. We came for the crunch, and he’s giving it to us. The Strat roars through Sugar’s “Hoover Dam,” then a series of solo tracks. The better-known of these have the most crowd impact, as is to be expected. “See a Little Light” in particular, a cheery anomaly in the bleakness and despair of his earliest solo work, brings the audience to its feet.

I wish he’d talk more. I wish he’d tell some stories. He isn’t going to do that, because that would be too rock star. Too much ego. He’s much more comfortable with the spotlight these days, finds the adulation easier, but for him the song is the thing. If we want stories, there are plenty of interviews and features on Youtube. This is about the music.

Eventually, though, he does pause. The Strat needs tuning, at long last, and Bob’s got something on his mind. He’s been in Berlin for three years, and he wants to know what the fuck has happened to American politics since he’s been gone. I’m a bit nervous: he makes it plain he has no patience for the current White House occupant and the values that man seems to represent—no surprise there, as what set Hüsker Dü apart from their ideologically hardcore, politically ranting peers was their compassion, their empathy, their introspection, and their willingness to sing about feelings to a drunken, violent crowd. Louisville leans left, to be sure, but this is, after all, Kentucky. I brace for pushback. None comes. Bob concludes: “it doesn’t matter who you vote, but please, do vote, and”—holding his hands to his heart—”vote from here.” Applause. We’re all in this together.

Back to it, then. The career retrospective continues, and Sugar’s “If I Can’t Change Your Mind” earns special praise: this crowd is 300-odd balding, greying ex-rockers with expanding waistlines remembering the days when college radio was important, when “alternative” and “indie” actually was, and when liking the right music meant you were on the right path in life. I’m getting a bit overcome with nostalgia myself. I know exactly where I was when I first heard that song, when he released that album. Bob himself doesn’t have time for this nonsense. He’s not dead yet: the voice is still strong, the fingers still nimble, and wipe your damned eyes—we’re into the encore.

I say “encore.” He doesn’t leave the stage. Just stands in the back corner for a moment while we shout and hoot for more. He’s smirking, shaking his head. Can you believe, after all these years, I can still make a living at this? No more than a minute passes, and he’s back to the mic. He slows down the tempo, for the first and only time tonight. It’s “Hardly Getting Over It,” from the Hüskers’ first Warner release, Candy Apple Grey, circa 1986. It’s a lovely song, full of sadness and beauty, but for many, it marked the beginning of the end of Bob’s first band, and in some ways the death of an entire sound. Not even two years later the Dü would be kaput, dissolved into addiction, ill health, and lawsuits. The establishment always wins in the end, doesn’t it? I don’t miss the drums here; Grant Hart was never going to be a first-call drummer for a tender, contemplative pop ballad. It’s a song better unadorned. But now that I am thinking about Grant, who died two years ago, almost to the very day…

“Never Talking to You Again.” It’s one of Grant’s tunes. I may start crying. It may be that Bob and Grant made peace before the end, but I don’t know that they did. Some wounds don’t heal, ever. And this is a bitter song: “tired of wasting all my time / trying to talk to you,” Grant sang, over sparse accompaniment. It could be taken as a final fuck-off, here, tonight, in this venue. But it isn’t. It’s gentle, rueful. They were mates, once. No, we won’t be talking to you again. But I sure wish we could, man.

Whew. We take a breath, and Bob thanks us again for being us. (No, Bob, thank you for being you.) That silver Strat has been worked tonight. Does it have anything left to give? Crunch: yep, sure does. From the last SST release, Flip Your Wig: “Makes No Sense at All.” The old and grey are all singing along to this one. “Makes no DIFFerENCE at all! Makes no sense at all!”

It doesn’t make sense. None of this makes sense. Life doesn’t make sense. All we can do is keep singing our songs, keep playing our guitars, keep trying to be better than we were the last time around.

A prolonged ovation and the house lights rise. Bob’s gone. The road beckons.

A note: Journeyman tunesmith Will Johnson opened the show, performing his brand of plaintive folk and Americana with a strong voice and humble bearing. There seemed to be centuries of wisdom in him; I pegged his age at somewhere between 30 and the Civil War. At one point, my seat-neighbor remarked, “That’s a man who’s had his heart broken.” It was a compliment.

Not this exact show, but a few days previous at Riotfest: